So, today we played Session 2 of Annalise. We had two tables. The table I was at decided to give our story one more session next week. The other table wrapped theirs up today. Since my table’s story is in progress, I won’t comment on that just yet. I’m going to take this time to talk a bit about the rules.

Mechanically speaking, Annalise is terrific. The idea behind the game is there is a ‘vampire’ who is trying to turn the player characters into its thralls. Now, the vampire doesn’t have to be a literal nosferatu, nor does it even have to be an individual. It can be a concept, like ‘drug addiction,’ or a group of people, like a cult. At the start of the game, you don’t know the identity of the vampire. During play there may be hints in the story as to what the vampire is, but ultimately the game’s mechanics allow for the vampire to reveal itself organically through play.

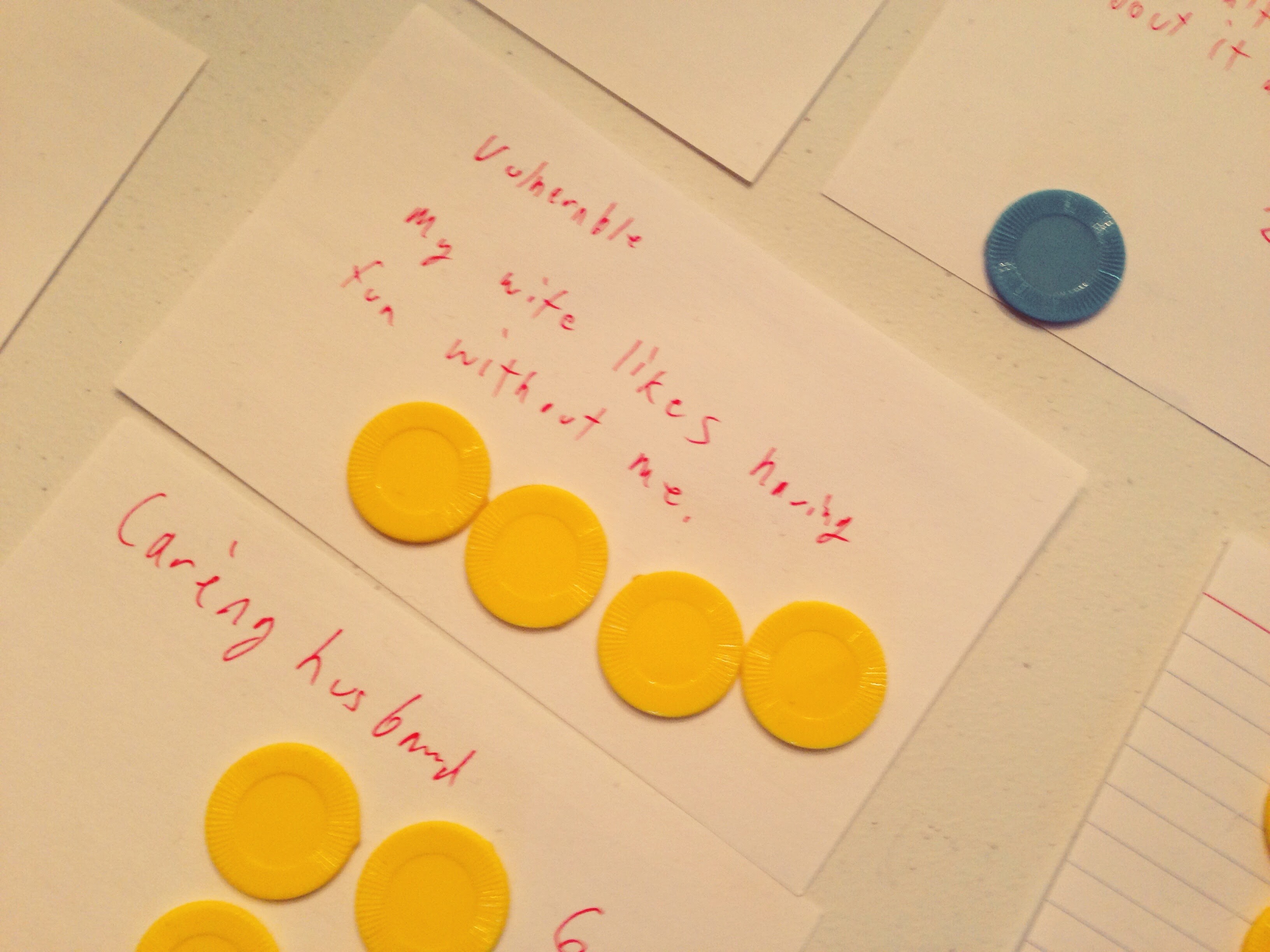

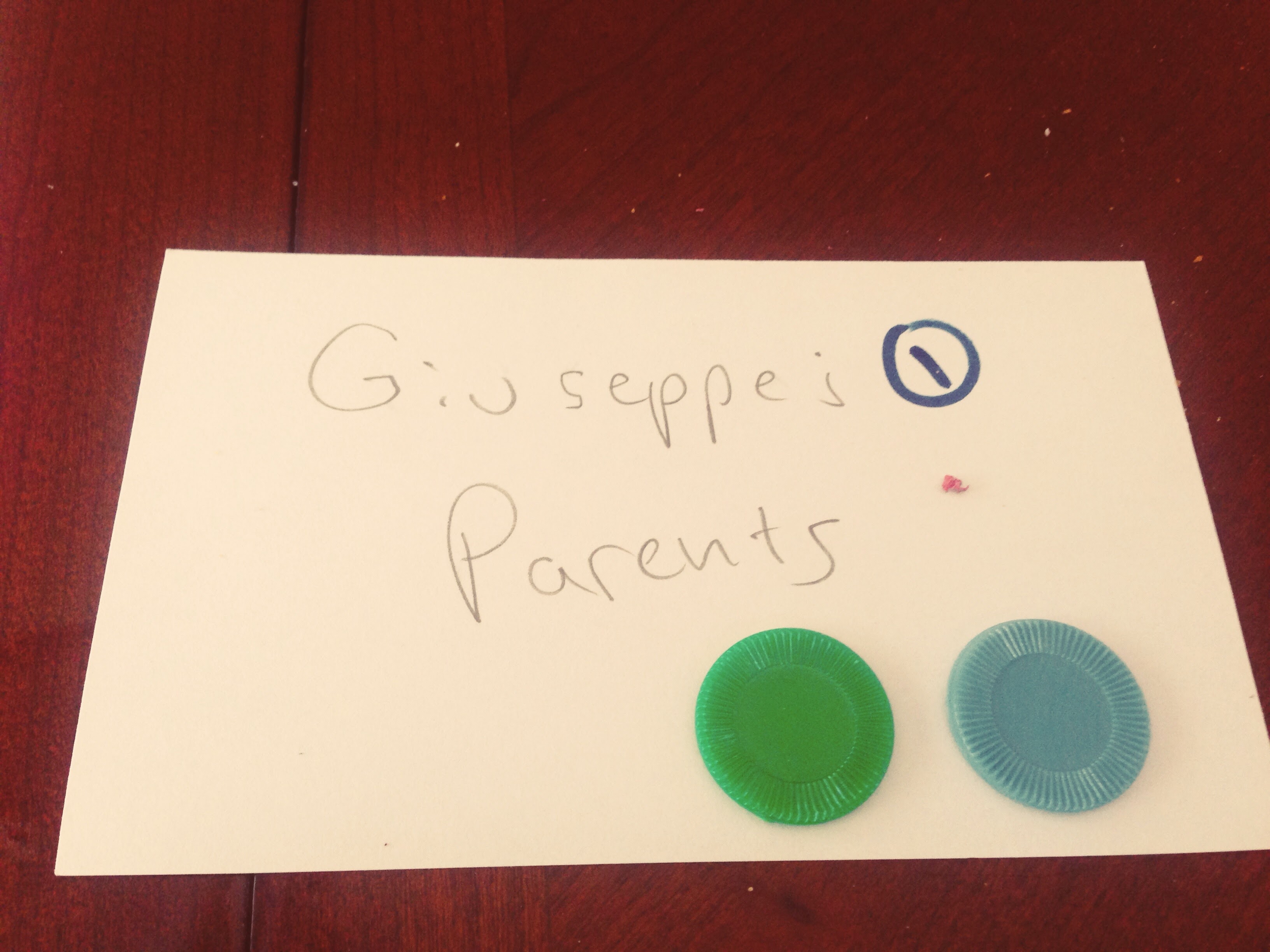

Player characters have a Vulnerability and a Secret. Their Vulnerability is the thing that makes them particularly susceptible to being lured-in by the vampire, and they can write traits that are related to it. Their Secret is a piece of dark information that the player can hint about throughout the game by making traits that allude to it. Players may also claim interesting ideas in the story as a sort-of currency which can be used to push the story in different directions. So, for example, if my narration involves my character’s love of opera, another player can claim ‘The Opera’ and then narrate it in later to affect things.

Gameplay involves setting scenes and playing them out until the spotlight player states something they want to achieve as an objective. Their scene guide (another player at the table) then details a consequence. The resolution mechanic involves tapping the traits gained from your Secret and your Vulnerability and then rolling to see if either the objective or the consequence comes to pass. Other players can narrate-in their claimed story elements to manipulate the outcome as well.

I can’t speak much to the endgame, because our table isn’t there yet, but I gather at some point the vampire reveals itself and then everyone has to make a choice about whether they succumb to it or resist it.

I really love this game. It is just so damn cool. I’m very happy that our table decided to take a third session to finish the story, because I didn’t want to rush it. We’re letting our depraved, nightmarish little tale unfurl at a really elegant pace, and I’m quite happy with it.

If anyone else wants to chime-in with their thoughts, please do.

Thanks to Jessica Scott and Aaron Scott for facilitating the games. They’re a fairly new addition to the Gauntlet, and we’re super-glad they joined us.

Thanks also to Rob Ferguson Ferrell Riley Steve Mains and Angel Ludwig for coming out!

Submission for No-Context Theater:

I cock-blocked my childhood friend by sticking my head in a horses ass!

Submission for No-Context Theater:

I cock-blocked my childhood friend by sticking my head in a horses ass!

Ferrell Riley No context theater, indeed!

Ferrell Riley No context theater, indeed!

Sounds like a whole lot of fun (the game, not head spelunking in horse anus)!

Sounds like a whole lot of fun (the game, not head spelunking in horse anus)!

Sean Smith it was a Trojan horse, if that makes you feel better, haha.

Sean Smith it was a Trojan horse, if that makes you feel better, haha.

So I mentioned most of this on the day, but figured I’d come on here and play #HailSatan ‘s advocate anyway. I was about an hour and a half into typing up my thoughts when a single errant mouse click utterly and irrevocably deleted what I was typing. No more using Gmail’s autosaving a draft to type something up. So this is gonna be holy-shit way way way shorter than what I had initially intended.

Ready?

Annalise sucks goat balls.

OK, that’s the wasted time and effort talking. I had fun, but am not as enamored with Annalise as all that.

It’s too fiddly. Cheat sheets would help a lot (and points for them being up on the website), but it’s still too weighted down by lingo and rules for its own good.

Secrets in the game are at best unnecessarily kept hidden from other players, and are at worst disruptive and bizarre ways to slip superpowers into the tail end of a vampire game for some fucking reason. Surprise! Our game’s about cyborgs now!

“Moments,” which are the game’s conflict/scene resolution, are basically a big, confusing pause button on the game where nothing definite happens in the fiction–nothing gets narrated in–but where all the players talk about and negotiate what might, possibly–if you’re lucky or unlucky–happen in the scene, maybe, and also this thing, but not that thing anymore and nevermind, it’s back. And then, as if that weren’t confusing enough, one person narrates how the potential good things do or don’t happen, and another narrates how the potential bad things do or don’t happen. Furthermore, if there’s something especially interesting or contentious about to go down, that pause button where nothing really happens can last for a good ten minutes or so, if our experience is an indicator.

Only in the endgame do new Claims–encouragement for reincorporation of the story’s elements–stop coming into play. Even though the game wants you to reincorporate things, it tends to reincorporate new things in lieu of older, established ones.

The game feels like it has two fairly distinct halves. The second half is dealing with the vampire. Cool. The first half is a meandering look at characters where eventually the hope is you’ll stumble upon some sort of vampire thingy or other? And maybe it’ll make some sense somehow? Even though I think we did a decent job of bringing it all together, it’s all pretty loosely connected at best. All these mechanics to deal with Moments and Claims and basically bupkis to deal with what the game’s supposed to be about. Shit could be seriously tightened up.

I’d give Annalise another go. Still, the cover of the book says “Final Edition,” and I think that’s a shame.

So I mentioned most of this on the day, but figured I’d come on here and play #HailSatan ‘s advocate anyway. I was about an hour and a half into typing up my thoughts when a single errant mouse click utterly and irrevocably deleted what I was typing. No more using Gmail’s autosaving a draft to type something up. So this is gonna be holy-shit way way way shorter than what I had initially intended.

Ready?

Annalise sucks goat balls.

OK, that’s the wasted time and effort talking. I had fun, but am not as enamored with Annalise as all that.

It’s too fiddly. Cheat sheets would help a lot (and points for them being up on the website), but it’s still too weighted down by lingo and rules for its own good.

Secrets in the game are at best unnecessarily kept hidden from other players, and are at worst disruptive and bizarre ways to slip superpowers into the tail end of a vampire game for some fucking reason. Surprise! Our game’s about cyborgs now!

“Moments,” which are the game’s conflict/scene resolution, are basically a big, confusing pause button on the game where nothing definite happens in the fiction–nothing gets narrated in–but where all the players talk about and negotiate what might, possibly–if you’re lucky or unlucky–happen in the scene, maybe, and also this thing, but not that thing anymore and nevermind, it’s back. And then, as if that weren’t confusing enough, one person narrates how the potential good things do or don’t happen, and another narrates how the potential bad things do or don’t happen. Furthermore, if there’s something especially interesting or contentious about to go down, that pause button where nothing really happens can last for a good ten minutes or so, if our experience is an indicator.

Only in the endgame do new Claims–encouragement for reincorporation of the story’s elements–stop coming into play. Even though the game wants you to reincorporate things, it tends to reincorporate new things in lieu of older, established ones.

The game feels like it has two fairly distinct halves. The second half is dealing with the vampire. Cool. The first half is a meandering look at characters where eventually the hope is you’ll stumble upon some sort of vampire thingy or other? And maybe it’ll make some sense somehow? Even though I think we did a decent job of bringing it all together, it’s all pretty loosely connected at best. All these mechanics to deal with Moments and Claims and basically bupkis to deal with what the game’s supposed to be about. Shit could be seriously tightened up.

I’d give Annalise another go. Still, the cover of the book says “Final Edition,” and I think that’s a shame.

Steve Mains I can definitely see how a dyed-in-the-wool story gamer could reach some of those conclusions. As an equally dyed-in-the-wool story gamer, I’ll expand on my impressions of the game a little bit, and why I liked it.

When it comes to a game, especially a fiddly one like this, I ask myself “Did these rules help us achieve something in the story that we could not have achieved without them?” If the answer is no, then that’s a game I probably want to part ways with. A classic, recent example at our table is Kingdom. That’s a very fiddly game that, while we have had fun with it at times, doesn’t really justify its own existence. Many games get you to the same place as Kingdom with a lot less fuss.

Our (ongoing) game of Annalise is about 16th century Venetian nobles and the politicking and debauchery they get up to. We could definitely tell that story in any of a number of games, but I think Annalise brought something special to the proceedings in the form of the Claims. We found the Claims to be an excellent way of exploring themes and incorporating symbolism into the story. That’s pretty high-level, authorial stuff that doesn’t normally happen in a story game (nor does it need to – I am merely suggesting it is a cool outcome in Annalise). Some examples: One of our claims is “A slash of red on white.” Now, that particular claim has been brought-up in several different contexts, and it’s always really cool when it happens. Sometimes it’s just a literal description of someone’s gown; other times it’s more symbolic, like when it was used to push a Moment toward a bloody outcome. Another one of our claims is “Helen of Troy.” That single Claim has helped us craft a story that incorporates visual elements of Greek mythology, as well as sort-of pushing our story into being something of a twisted, metaphorical re-telling of the siege of Troy (one of the character’s family name is Troya).

We have ended-up with a very high-level story (it has been remarked more than once that we could see our story being on HBO, for example). Part of the reason is the conflict resolution that you perceive as a bug, but that I perceive as a feature. Does it take you out of the roleplaying for a few minutes? Yes. But the way our table has handled it has been very satisfying, which is to say it has been like three screenwriters engaged in a collaborative process. When someone is using their Claim to push a Moment in a certain direction, we don’t go back and forth on it too much because we often like the place that person is taking the story, to the point where we would even use our own claims to go against our character’s interest because it is more intriguing than what we had originally envisioned. And that leads to my final point…

All story games, but perhaps especially so Annalise, require everyone at the table to play in the spirit of the story being told. Yes, it’s true that someone could be an asshole and introduce X-Men powers into the Secrets, but 1) that person would definitely be violating the spirit of the game if you decided ahead of time what your game was going to be about and 2) it doesn’t really matter because, as explained to us by Jessica, you can request another secret if you don’t like the one you’ve been given. This comes up from time-to-to-time – the idea that one player at the table could use a game’s rules to derail things for everyone else – but I don’t think it’s a legit argument about the quality of the game. For one thing, an asshole will always find a way to do this, no matter how mechanically tight the game is. Another thing – why hasn’t that player been shown the door already?

I know Rob will disagree with me mightily on this, but establishing and maintaining tone is important. It’s important because it keeps the fiction honest and it makes things just go down smoother. The story we’re telling at our table is probably one of the most elegant and satisfying I’ve had in a good long while. Part of that is because we all started on the same page and we’re being respectful of the established tone. As such, I think we’ve been able to get a lot out of the game’s rules, as described above.

Steve Mains I can definitely see how a dyed-in-the-wool story gamer could reach some of those conclusions. As an equally dyed-in-the-wool story gamer, I’ll expand on my impressions of the game a little bit, and why I liked it.

When it comes to a game, especially a fiddly one like this, I ask myself “Did these rules help us achieve something in the story that we could not have achieved without them?” If the answer is no, then that’s a game I probably want to part ways with. A classic, recent example at our table is Kingdom. That’s a very fiddly game that, while we have had fun with it at times, doesn’t really justify its own existence. Many games get you to the same place as Kingdom with a lot less fuss.

Our (ongoing) game of Annalise is about 16th century Venetian nobles and the politicking and debauchery they get up to. We could definitely tell that story in any of a number of games, but I think Annalise brought something special to the proceedings in the form of the Claims. We found the Claims to be an excellent way of exploring themes and incorporating symbolism into the story. That’s pretty high-level, authorial stuff that doesn’t normally happen in a story game (nor does it need to – I am merely suggesting it is a cool outcome in Annalise). Some examples: One of our claims is “A slash of red on white.” Now, that particular claim has been brought-up in several different contexts, and it’s always really cool when it happens. Sometimes it’s just a literal description of someone’s gown; other times it’s more symbolic, like when it was used to push a Moment toward a bloody outcome. Another one of our claims is “Helen of Troy.” That single Claim has helped us craft a story that incorporates visual elements of Greek mythology, as well as sort-of pushing our story into being something of a twisted, metaphorical re-telling of the siege of Troy (one of the character’s family name is Troya).

We have ended-up with a very high-level story (it has been remarked more than once that we could see our story being on HBO, for example). Part of the reason is the conflict resolution that you perceive as a bug, but that I perceive as a feature. Does it take you out of the roleplaying for a few minutes? Yes. But the way our table has handled it has been very satisfying, which is to say it has been like three screenwriters engaged in a collaborative process. When someone is using their Claim to push a Moment in a certain direction, we don’t go back and forth on it too much because we often like the place that person is taking the story, to the point where we would even use our own claims to go against our character’s interest because it is more intriguing than what we had originally envisioned. And that leads to my final point…

All story games, but perhaps especially so Annalise, require everyone at the table to play in the spirit of the story being told. Yes, it’s true that someone could be an asshole and introduce X-Men powers into the Secrets, but 1) that person would definitely be violating the spirit of the game if you decided ahead of time what your game was going to be about and 2) it doesn’t really matter because, as explained to us by Jessica, you can request another secret if you don’t like the one you’ve been given. This comes up from time-to-to-time – the idea that one player at the table could use a game’s rules to derail things for everyone else – but I don’t think it’s a legit argument about the quality of the game. For one thing, an asshole will always find a way to do this, no matter how mechanically tight the game is. Another thing – why hasn’t that player been shown the door already?

I know Rob will disagree with me mightily on this, but establishing and maintaining tone is important. It’s important because it keeps the fiction honest and it makes things just go down smoother. The story we’re telling at our table is probably one of the most elegant and satisfying I’ve had in a good long while. Part of that is because we all started on the same page and we’re being respectful of the established tone. As such, I think we’ve been able to get a lot out of the game’s rules, as described above.

A couple more things I liked…

The idea of achievements and consequences, and the way they can occur independently of one another. This leads to some very interesting, often unforeseen, outcomes in the story.

The role of the Scene Guide. Perhaps it’s because our setting is so ornate and inherently sensual, but we have treated the role of the Scene Guide as an almost sacred duty to bring the details of the scene alive for the other players. The sounds, the smells, the sights…that sort of thing. We take some time to linger on those things, and it’s very satisfying.

These two things, along with the basic thrust of conflict resolution, as described in my earlier post, leads me to believe this is a game less about inhabiting a character and more about crafting a story in a collaborative way.

A couple more things I liked…

The idea of achievements and consequences, and the way they can occur independently of one another. This leads to some very interesting, often unforeseen, outcomes in the story.

The role of the Scene Guide. Perhaps it’s because our setting is so ornate and inherently sensual, but we have treated the role of the Scene Guide as an almost sacred duty to bring the details of the scene alive for the other players. The sounds, the smells, the sights…that sort of thing. We take some time to linger on those things, and it’s very satisfying.

These two things, along with the basic thrust of conflict resolution, as described in my earlier post, leads me to believe this is a game less about inhabiting a character and more about crafting a story in a collaborative way.

It feels like our table had a different group synergy than the other. I always noticed that even when one of the 3 of us wasn’t either active or storyteller, we were still involved in the storytelling process, sprinkling a detail or making a suggestion. It might be that element that makes for such a different game, as having even one player who is either not involved, or being disharmonious, can ruin the crystal structure of the entire narrative. As has been brought up, having the “X-Man Secret” written by someone who really really wants their eyebeams in the game.

Honestly for ours, I think we all settled for some sort of opera the moment we started the game in an agreed and unconscious fashion. I can see quite a few of the scenes up on a large stage set to music

It feels like our table had a different group synergy than the other. I always noticed that even when one of the 3 of us wasn’t either active or storyteller, we were still involved in the storytelling process, sprinkling a detail or making a suggestion. It might be that element that makes for such a different game, as having even one player who is either not involved, or being disharmonious, can ruin the crystal structure of the entire narrative. As has been brought up, having the “X-Man Secret” written by someone who really really wants their eyebeams in the game.

Honestly for ours, I think we all settled for some sort of opera the moment we started the game in an agreed and unconscious fashion. I can see quite a few of the scenes up on a large stage set to music

In the game’s defense, part of my problem with the game could have pretty easily been taken care of if we’d just sat down for like five minutes before playing and settled on a setting. Everything we ended up with I would have been fine with had we actually talked about it beforehand. Small town in the old west, matriarchy, communal, some smattering of supernatural weirdness besides the vampire, and more-or-less standard vamp? Sweet, let’s do it. I should have figured that establishing everything from square one as we went would bug me and suggested a little pre-game consensus, so my bad. If I played again, I’d definitely try to get everyone in at least the same chapter, if not on the same page.

But if I’m not mistaken (though I very well could be; someone correct me if I’m wrong), this style of play is explicitly supported by the game. As such, especially combined with the book’s suggested secrets, the person who wants to throw some teleportation into the mix as a secret is not a jerk, but is just playing the game as written. Again, if I were to play again, what sorts of things are and aren’t up for grabs is a topic to briefly cover pre-game, I’d say.

Secret superpowers in the game wouldn’t be quite as weird except the game encourages them to only be revealed later in the game–likely the endgame–if at all. So it’s not even like at the start of the game I flip my “I’m secretly Iron Man” card over and everyone realizes what just got introduced to the game. I have my “I’m secretly Iron Man” card, and it stays a secret, known only to me and at best guessed at by the others, who have no idea such a thing is possible, let alone an in-game reality. S’weird.

[Edit: I didn’t realize that surrounding a word with hyphens struck through it, so there was a very confusing paragraph up there until I got home from work. Sorry!]

In the game’s defense, part of my problem with the game could have pretty easily been taken care of if we’d just sat down for like five minutes before playing and settled on a setting. Everything we ended up with I would have been fine with had we actually talked about it beforehand. Small town in the old west, matriarchy, communal, some smattering of supernatural weirdness besides the vampire, and more-or-less standard vamp? Sweet, let’s do it. I should have figured that establishing everything from square one as we went would bug me and suggested a little pre-game consensus, so my bad. If I played again, I’d definitely try to get everyone in at least the same chapter, if not on the same page.

But if I’m not mistaken (though I very well could be; someone correct me if I’m wrong), this style of play is explicitly supported by the game. As such, especially combined with the book’s suggested secrets, the person who wants to throw some teleportation into the mix as a secret is not a jerk, but is just playing the game as written. Again, if I were to play again, what sorts of things are and aren’t up for grabs is a topic to briefly cover pre-game, I’d say.

Secret superpowers in the game wouldn’t be quite as weird except the game encourages them to only be revealed later in the game–likely the endgame–if at all. So it’s not even like at the start of the game I flip my “I’m secretly Iron Man” card over and everyone realizes what just got introduced to the game. I have my “I’m secretly Iron Man” card, and it stays a secret, known only to me and at best guessed at by the others, who have no idea such a thing is possible, let alone an in-game reality. S’weird.

[Edit: I didn’t realize that surrounding a word with hyphens struck through it, so there was a very confusing paragraph up there until I got home from work. Sorry!]

Steve Mains I haven’t read the rules, so you may be correct about the game allowing for a certain type of set-up and play. That said, it seems like it would be unfair for everyone at the table if we just have to go in the direction of whoever gets the ball rolling. I like to talk a little bit about what we’re embarking on. That doesn’t mean we have to go into a lot of detail or workshop the thing, but it just means getting everyone on the same page. Even a game that has a pre-determined setting deserves a conversation about tone.

On a side note, I have noticed that some game authors will use very silly examples as a means of illustrating their mechanical point. Take, for instance, Misspent Youth. Everything about the presentation of that game screams “Young punk rock kids in a violent dystopian future.” But, in the rules, all the examples are Star Wars. The game is clearly not meant to be Star Wars, but the author decided that would be easier for people to understand when it comes to mastering the rules. I think something similar might be happening with Annalise. Nothing about the aesthetic of the book suggests super-powers, but maybe the author thought those might be good for understanding the concept of ‘Secrets’ in the game.

Steve Mains I haven’t read the rules, so you may be correct about the game allowing for a certain type of set-up and play. That said, it seems like it would be unfair for everyone at the table if we just have to go in the direction of whoever gets the ball rolling. I like to talk a little bit about what we’re embarking on. That doesn’t mean we have to go into a lot of detail or workshop the thing, but it just means getting everyone on the same page. Even a game that has a pre-determined setting deserves a conversation about tone.

On a side note, I have noticed that some game authors will use very silly examples as a means of illustrating their mechanical point. Take, for instance, Misspent Youth. Everything about the presentation of that game screams “Young punk rock kids in a violent dystopian future.” But, in the rules, all the examples are Star Wars. The game is clearly not meant to be Star Wars, but the author decided that would be easier for people to understand when it comes to mastering the rules. I think something similar might be happening with Annalise. Nothing about the aesthetic of the book suggests super-powers, but maybe the author thought those might be good for understanding the concept of ‘Secrets’ in the game.

Uhh. Speaking from personal experience, he may have been mistaken.

My posting about Annalise has largely been negative. That’s a result of all the good things I was saying as I originally typed everything up getting accidentally wiped out. After this, I figured I should mention the negatives because others already covered the positives.

I do really like the non-intersecting achievements/consequences and the concept of claims, even if I wish they were a little more focused toward horror and horrific imagery instead of just reincorporation.

I also wanna thank Rob Ferguson , Angel Ludwig , and Aaron Scott (whom I can’t for the life of me get G+ to recognize as a linkable user) for helping me to have fun even in a system I couldn’t properly engage with.

Uhh. Speaking from personal experience, he may have been mistaken.

My posting about Annalise has largely been negative. That’s a result of all the good things I was saying as I originally typed everything up getting accidentally wiped out. After this, I figured I should mention the negatives because others already covered the positives.

I do really like the non-intersecting achievements/consequences and the concept of claims, even if I wish they were a little more focused toward horror and horrific imagery instead of just reincorporation.

I also wanna thank Rob Ferguson , Angel Ludwig , and Aaron Scott (whom I can’t for the life of me get G+ to recognize as a linkable user) for helping me to have fun even in a system I couldn’t properly engage with.