Friday night, our table played two different #Threeforged games. Hopefully the other players involved will chime in with their thoughts. Russell Benner Daniel Fowler and Gauntleteer Sandra (whom I don’t know how to tag) all played.

First was A Hard Goodbye, a GM-less game about people trying to leave a brutal organization that isn’t so easy to quit.

The game starts off strong, with collaborative creation of the Organization the characters are all members of. Think mob, mercenary companies, gangs, thieves and assassins and the like. You also create a Threat that will cause problems for the Organization in Act II. We went with a Repo Men-like organ repossession corporation that specializes in selling alien organs. Our Threat was the aliens themselves, with shady motives and capabilities.

Character creation is next. I especially like the following: PCs have a Fate-like High Concept, a Hook that makes it difficult for your character to leave, and an Out–which is somebody pulling your character away from their life with the Organization. Character creation is nice and compact, giving your character an excuse for still being with the Organization even if they’re unhappy with it, plus a great excuse to leave.

Gameplay is spread out across three acts. In the first, PCs go on a mission for the Org. In the second act, PCs… go on a mission (or two), this time concerning a shakeup in the Organization brought on by the Threat. In the third, they try to make a break for it, or resign themselves to remaining in the Organization. I like the three act structure, but scenes themselves can be a bit odd.

Before an act’s scenes, players collaborate to come up with assignments for their characters. This would be fine, except it all happens simultaneously. Player 2 is giving an assignment to player one while receiving one from Player 3, who’s getting one from Player 4, who’s trying to listen to Player 1. It’s messy, and could stand some structure. Furthermore, the fact that all of this happens before play means that scenes cannot easily build upon preceding scenes, which seems like a missed opportunity to me.

The game handles its lack of a GM in a strange way. Players take turns being the Active Player, whose character is foremost in the scene. But the Active Player also sets the pace and drives their scene forward, delegating responsibility for helping out or playing NPCs as they like. Without a temp-GM or a Polaris-like division of authority, (and especially combined with the fact that the Active Player helps to collaborate in coming up with their assignment), this can start to feel a bit like hitting a tennis ball against the garage instead of playing an actual opponent. In play, it didn’t work very well. This was my biggest reservation about the game going in, so I wasn’t super surprised. For Act II, we cheated and switched to having the player to the right of the AP act as their adversary, which helped a bit.

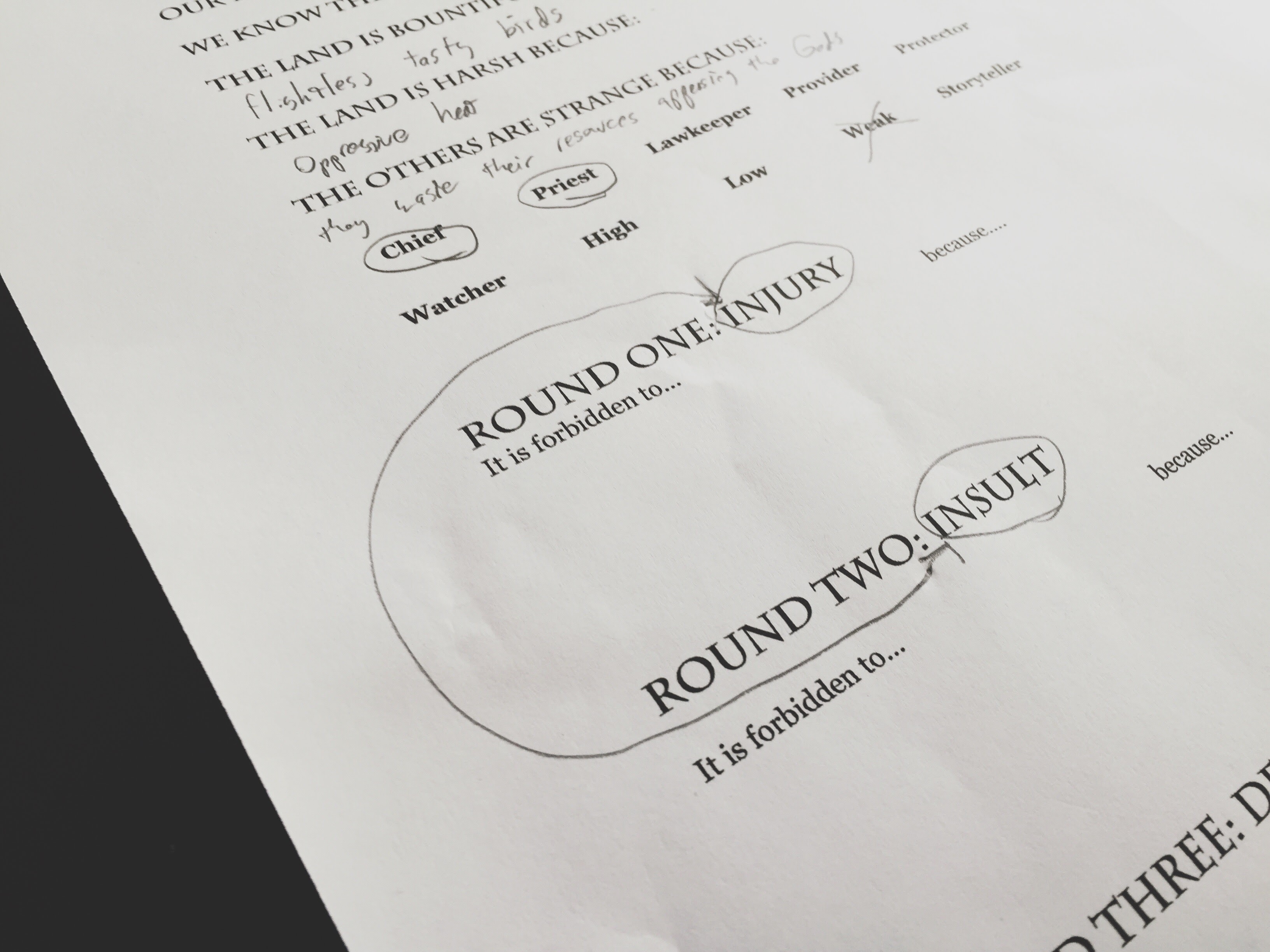

Once a scene reaches a tipping point, you go to the conflict mechanics. These are oddly specific, and differ from act to act. They’re so specific, in fact, that if you aren’t aiming for one when you start your scene, it’s very possible that you’ll come to what feels like a tipping point, and then spend a minute staring at the conflict types before relenting and going with something that’s ehhhh close enough, I guess. Each has a different method for determining a dice pool, and a unique effect on the game’s ever-changing stats, depending on success or failure. I like that the stats (those of the Organization and of the PCs) are constantly in flux. It makes it feel like the world is reacting to the characters. But with even one character acting to stay in the organization in Act II, Org stats will likely increase. It seems like it’s a serious stretch to expect anyone to be able to make it out if that’s the case.

A lot of the Act I conflict types seem like things that should have a bit more fictional setup before we get to them. “A Way Out,” “Opening Up,” “Drink to Forget,” “Informant,” “Russian Roulette,” and “Remembering a Friend” all feel a little premature. Like, we just met this person. We could use some status quo scenes before all of this. You can get a bonus for incorporating your character’s Out in a scene, but it seems like it would be difficult to shoehorn them in in the middle of an assignment (unless they are the assignment, which is an option).

Conflicts use competing dice pools. The handling time is high, but not a deal-breaker. If there were ever a tie, however, then you roll the dice again, rearrange them in descending order–by color–again (which is what the game requires), and then a few other fiddly things. Again. Uuuuugh. Not OK.

Overall, it shows some promise, but still needs plenty of work. Luckily, it’s good thematic fodder for a game, and some of the ideas are very strong.

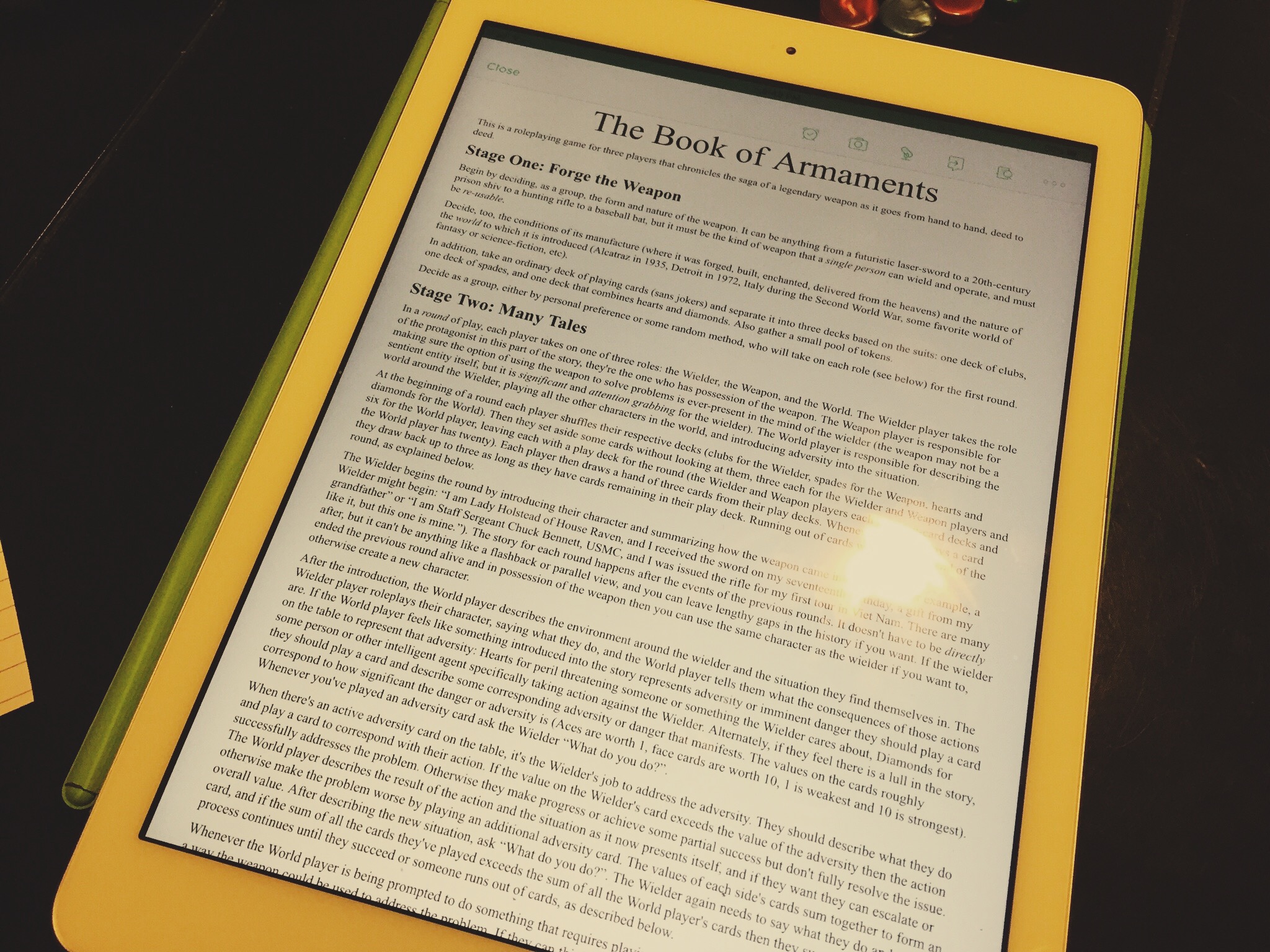

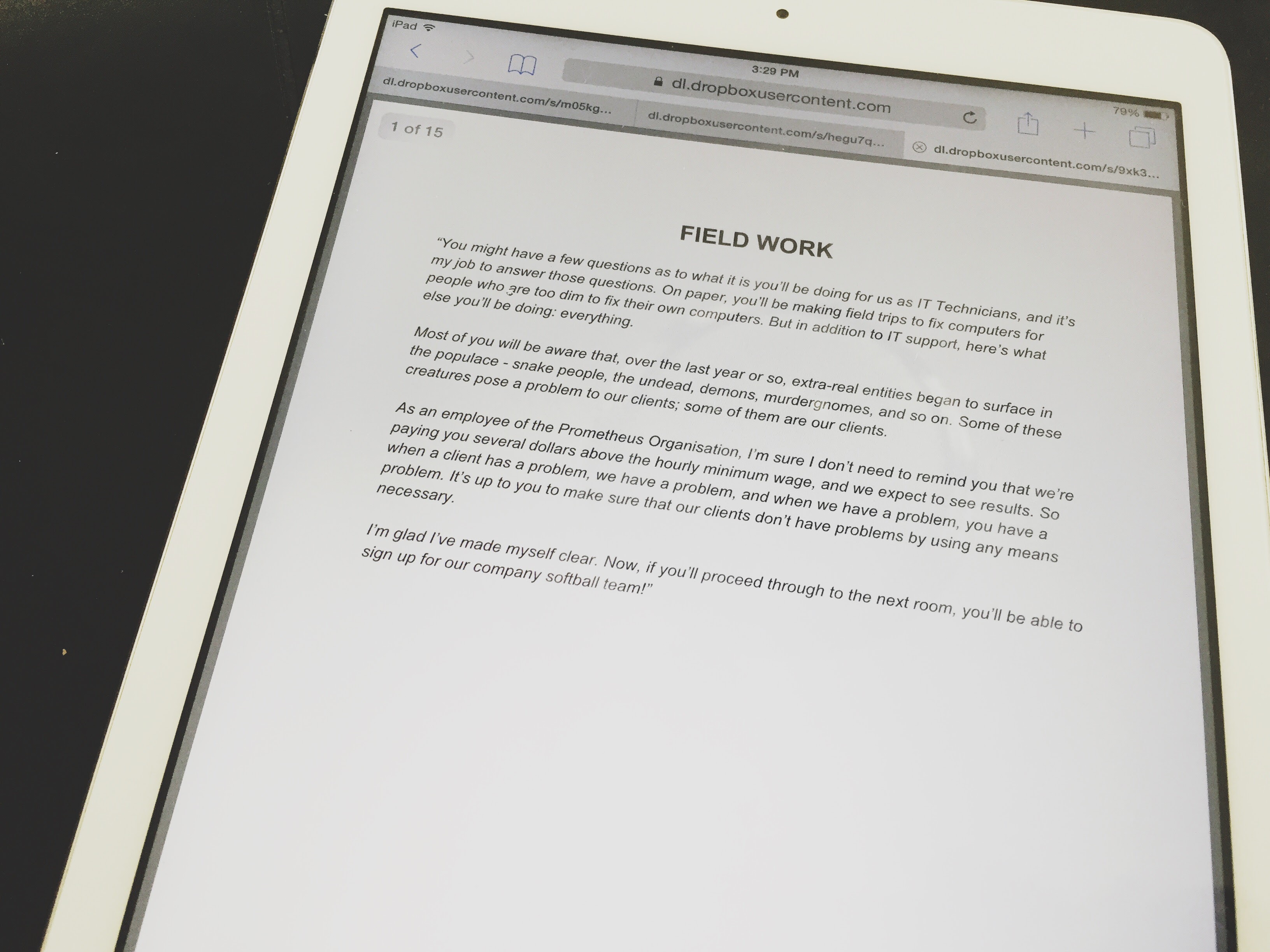

Next, we played Psychic Detective Agency. PDA is billed as an American freeform LARP, but we just played it as a tabletop game. Take what I say with a few grains of salt here, but there aren’t any mechanics that really require it be a LARP.

Players play either psychic detectives or audience members. There are three types of psychic detectives. The postcog can see into the past. The empath can sense what happens at it happens. The precog can see the future. At any time, anyone can pose a question to the other players. The postcog answers any questions about the past, the empath any about the present, and the precog any about the future. When a psychic is answering one of these questions, they hold their fingers to their temple as if in concentration, or hold their hand to the side of their mouth if it’s out of character. Love that. If a psychic isn’t present in the game (you’re supposed to have one psychic for every audience member player), then any audience member can answer a question that would normally be that psychic’s purview.

Players play out ever-changing scenes, introducing facts and asking/answering questions. The mystery at the core of everything expands outward, and in our case sort of got away from us. With so many facts and names coming up out of nowhere, it’s easy to get lost and forget who this character is, how we learned that they’re dead now, whether or not we know who killed them, and also are they the murder we’re investigating here or a separate killing? It gets pretty crazy, but that can be fun. I think that’s the sort of thing we’d get better at with multiple plays.

What bugs me, though, is that it’s very easy for the game to devolve into nothing but asking and answering questions, leaving most of the actual roleplaying out of it. Again, we’d probably get better at that too, but it feels like something’s missing. Scene structure? A limit on questions per scene or per player? I’m not sure. We had fun, but this one also definitely needs some work.

I need to give the game some serious props for the extras and advice in the rules. It talks about improv fundamentals, introduces cutting and braking, and provides sample questions and settings. It even has lists of detective tropes and names, plus an extended example of play. Kudos. It’s all very welcome.